Female healthcare consumers have a tremendously powerful voice in healthcare. Women make a whopping 80 percent of healthcare buying and purchasing decisions. Women are 76 percent more likely than men to have visited a doctor within the past year. Women even pick up three in four prescriptions.

Female healthcare consumers are more active and engaged than men in all things healthcare, which likely means they have a deeper view into the healthcare system’s nitty gritty. So, what do women think about the healthcare they’re receiving? Well, we have good news and bad news. According to our 2018 Consumer Survey of US Healthcare, the bad news is that women are skeptical or frustrated with many parts of the overall healthcare industry, but the good news is that they have specific ideas of how they would like to see it change.

Here’s more on what we learned, and what we think it means.

Women are Less Satisfied with Their Insurance, Insurers, and Providers. And They’re More Open to Taking Matters into Their Own Hands.

Women generally have less favorable opinions about their health insurance compared to men. Women were less likely to think their insurance was affordable (-5 points), valuable (-4 points), easy to understand (-4 points), and easy to use (-4 points). Notably, the biggest difference we noticed was around how tailored health insurance is to personal needs; women were 7 points less likely than men to believe their health insurance was effectively tailored to them.

Women also just felt generally less favorable toward the healthcare organizations they work with on a day to day basis. Net Satisfaction Rankings were 9 points lower for females versus males for their health insurer (-2 versus +7), and 8 points lower for their local hospital (-12 versus -4).

Why may this be? Here are two theories.

First, female consumers who do more, know more…and knowing more isn’t always great when it comes to our current healthcare system. Women’s greater involvement and immersion in healthcare decision-making simply makes them more aware of how things work, and we all know that they often don’t work as well as they could. In addition, we found 57 percent of women versus 51 percent of men make healthcare decisions for someone other than themselves. Since women tend to have a more holistic, complex involvement in the healthcare system, they may have a better understanding of its deepest flaws, driving their overall lower positivity. It is perhaps one thing, for instance, to be a single man managing a relatively simple medical condition solo, but a woman managing the care of herself, her spouse, and three children under the age of 5 will be more exposed to the healthcare system’s convoluted hassles.

Second, female consumers’ voices aren’t (yet) well represented. Because there are traditionally more men than woman in high ranking clinical and executive positions – only 30 percent of healthcare’s C-suite and 13 percent of healthcare’s CEOs are female – this gender leadership gap may drive women’s collective perceptions of healthcare as less friendly, inviting, and personalized compared to men.

And this perception is based on real experience. According to various clinical studies, women in the emergency room having a stroke are 30 percent more likely to be misdiagnosed. Other research confirms a gender bias regarding coronary heart disease symptoms – women compared to men receive coronary heart disease diagnoses 15 percent versus 56 percent, cardiologist referrals 30 percent versus 62 percent, and cardiac prescriptions 13 percent versus 47 percent.

According to a recent Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative webinar, 65 percent of women with chronic pain felt physicians failed to take their pain seriously, and 45 percent of women said they’d been labeled as chronic complainers.

Women in pain, argued Harvard University, are less likely to get medication for that pain in a timely way, or indeed at all. For example, women wait 16 minutes longer in the emergency room to receive analgesics for pain medication. And women who have received coronary bypass surgery receive prescriptions for painkillers half often than men, thereby suffering greater and for longer periods of time compared to men.

Take John Guillebaud, Professor of Reproductive Health at University College London, who confirmed period pain is, well, the equivalent of having a heart attack. “Men don’t get it and it hasn’t been given the centrality it should have. I do believe it’s something that should be taken care of, like anything else in medicine,” he said. This may be driven by a combination of physicians discounting female pain and women simply bearing it without complaint, but the broader point is that the medical system could and should be more proactive around resolving issues women suffer from.

Our research found, perhaps not surprisingly given just a handful of dire statistics like these, that most women don’t trust their physicians with open arms. Only 38 percent of women compared to 48 percent of men say they’re “completely confident” in their physician, trusting this person’s opinion “without question”.

Women are more likely than men, we found, to take a proactive approach to their care – perhaps because women are more likely to find the answers they need on their own after not being taken seriously by medical professionals.

And, women are wanting to weigh opinions against each other. Forty-five percent of women say they like to “learn more to doublecheck” compared to 37 percent of males. And, 12 percent of women say they always seek a second opinion, compared to 10 percent of males.

Women Express More Health and Healthcare Frustrations Than Men Do

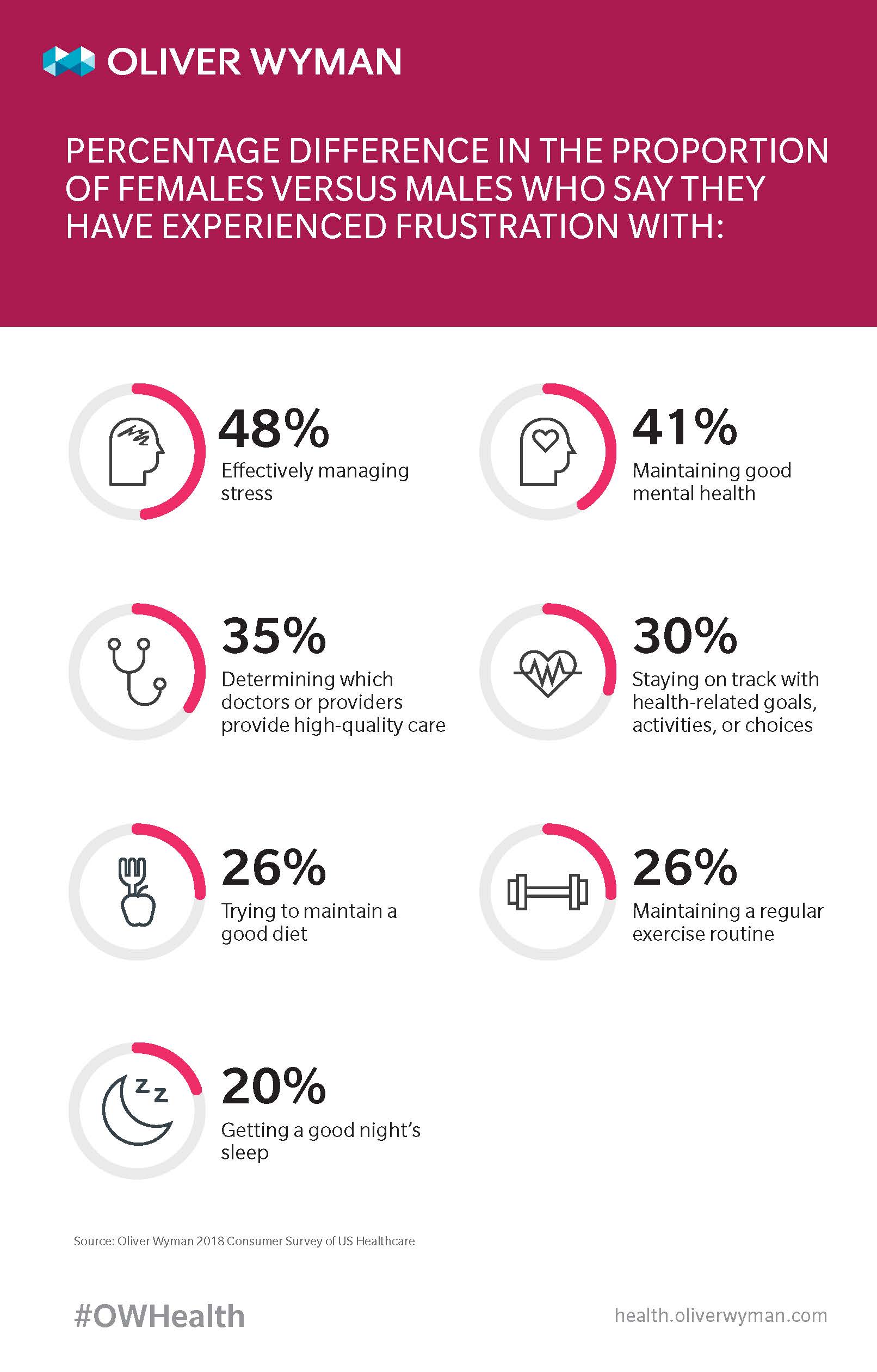

When we asked those consumers surveyed to rank their various frustrations, women were about 20 percent more likely than men to express at least mild frustration. However, women’s greater frustration is not evenly distributed. Women and men are equally frustrated with managing care costs – 36 percent of women versus 35 percent of men. However, when it comes to lifestyle-related frustrations like mental health, diet, exercise, and not getting enough sleep, women expressed significantly more frustration. According to our research:

Women are More Likely Than Men are to Explore and Learn About Their Health and Healthcare

Not content with just expressing frustration with the current state of the healthcare system, women are more likely to seek out emerging solutions to these frustrations. Importantly, we found this across a variety of example scenarios; women are not just more likely to latch onto one new gimmick or another, they are consistently more interested in exploring new options. In particular, we found women more often request healthcare services that help streamline the patient journey – they want care in more convenient settings (women are 33 percent more willing to receive advice and recommendations on general wellbeing through telehealth), they want care faster (women are 20 percent more likely to prefer “fast track” appointments with less wait time), and on their own terms (women are 10 percent more interested in accessing a physician or nurse via a help line). This is not just about women’s overarching desire to receive more general advice, as they have about the same willingness to receive this through a physician’s office (only a three percent difference), implying traditional services are being received uniformly across genders.

Findings like these may be linked to the fact that women are more often responsible for managing the complexities of an entire household – complicated and expensive healthcare and non-healthcare needs included – and are thus more eager to try out convenient, easy options that simplify their own lives, and the lives of their families and loved ones.

Broader Implications of Gender Differences

These numbers tell us the healthcare industry has a lot of work to do. Women are its primary consumers, so it should, cater to females more directly, by, for example helping them better manage their stress levels, fitness routines, healthy diets, and sleep habits. But it doesn’t.

That said, the healthcare system is operating in a society that puts more pressure on women in a broader sense. Women are conditioned and targeted at exponentially higher levels to put much greater effort, mind share, and energy expenditure into certain aspects of their health (the aspects that correlate with appearance, naturally) – like eating healthy (to look better), exercising (to look better), and buying that good or service (to feel better…by looking better). Women are generally “expected” to be more mindful of their health and wellness than men are – there’s no “swim trunk” season, for example. The irony here is one might argue this disconnect has led to men’s healthier mindsets and behaviors in the long run.

Beyond societal pressures, these results may also reflect how women tend to think more holistically than men do about their health. One health frustration or misstep may be tied to another, and then another. After all, if you’re not eating or sleeping well, chances are you probably haven’t done a sit-up in a while. In turn, your mental health probably isn’t exactly at peak performance. The connection between basic elements of life, like getting enough sleep and health outcomes, is real, and women have realized that faster than the healthcare industry has. Women are also moving faster when it comes to innovation. They are pushing for innovative services and are more likely to use them than their male counterparts are. When it comes to healthcare, the future really is female.

Women, who make the bulk of healthcare decisions, must be listened to with care, consideration, and compassion. It’s female-driven needs and wants – that faster and better technology, those shorter wait times, that less biased communication, and the basic right to be treated like a person, not another chronic complainer – that those in healthcare must proudly and boldly cater to moving forward to remain competitive, innovative, and on the leading edge of change. On this International Women’s Day, especially, we ask for no less.