Editor’s Note: Oliver Wyman recently participated in a National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation (NIHCM) webinar about addressing healthcare’s blind spot – overuse in medical care (view the entire webinar here). Below are some key highlights from this discussion where we explained how despite growing evidence that there’s still “too much” being done in healthcare, indications for specific technologies over time are indeed narrowing as we continue to learn about and implement improved care outcomes.

Today’s healthcare system lacks a way to measure appropriateness, aside from unscalable home-grown efforts. Physicians estimate over 20 percent of care is unnecessary. The annual cost of this waste? $265 billion, with 30,000 deaths a year caused by treatment that likely wasn’t even needed in the first place.

Consider the opioid epidemic. According to a study of over 18,000 patients, among those patients not taking opioids while receiving care in a hospital, over 45 percent were prescribed opioids when discharged. Similarly, among those surgeons performing a lumpectomy, we found most prescribe upwards of 20 opioids post-procedure (when experts at SolveTheCrisis.org agree a max of ten is appropriate). Yet, some patients still receive over 40 opioids post-procedure.

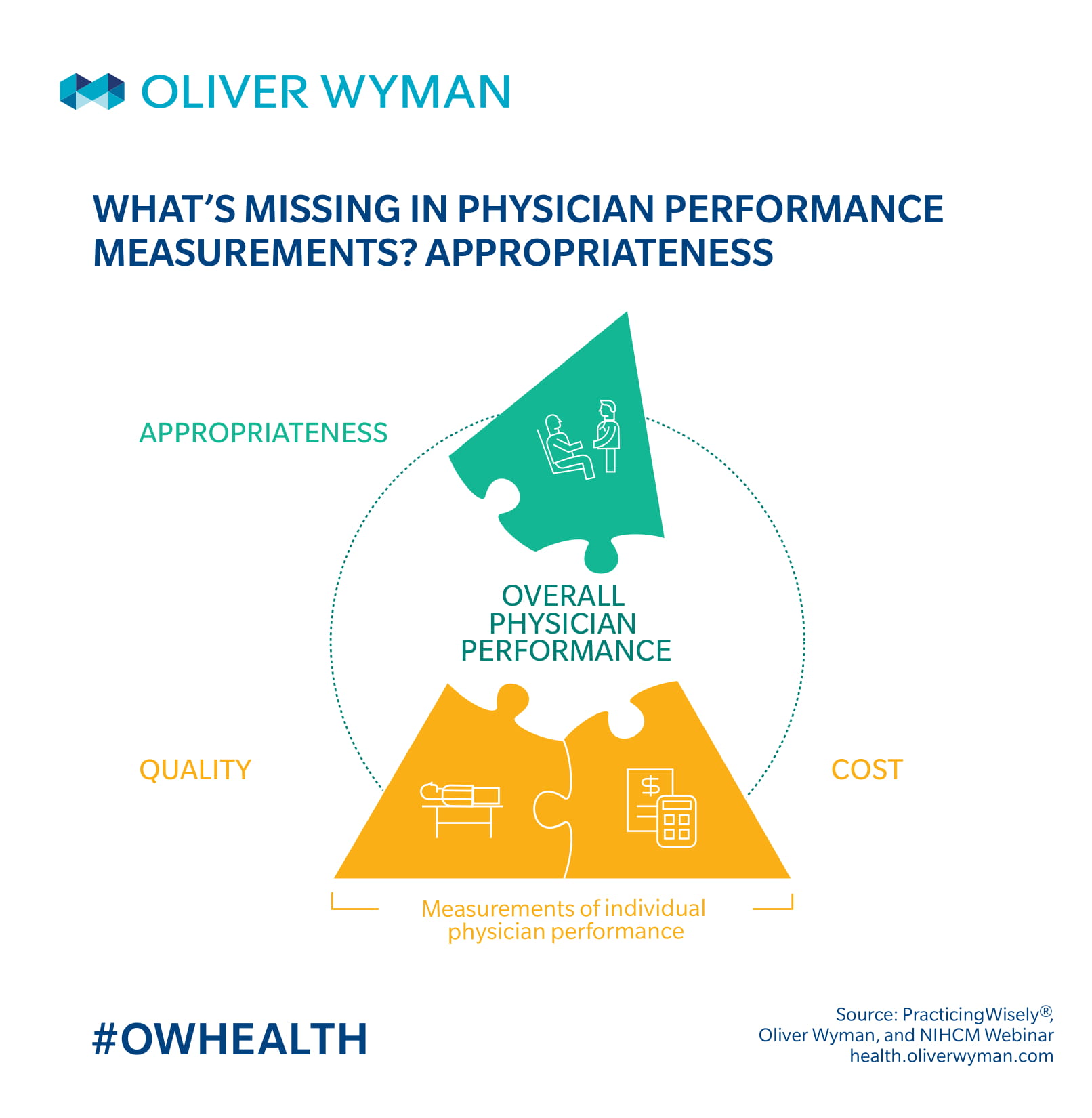

The Problem? There’s No Measuring Stick for Physician Appropriateness

The vast majority of physicians have good intentions and want to do the right thing for patients, but lack the tools to identify and curb unnecessary, expensive, and potentially harmful medical care. Physicians work in a system simply not designed to incent appropriateness. They are paid more to spend less time per patient in an industry that still rewards volume far more often than value.

Although metrics like readmission rates and episodic surgery costs do help measure physician performance, not many measures evaluate if the care was necessary or unnecessary in the first place, or whether a physician is habitually choosing a treatment approach that substantially deviates from his or her colleagues and from what guidelines suggest. Our measurement system has a massive blind spot when it comes to appropriate care.

Consider, for instance, how a patient experiences an episode in the healthcare system. A patient calls on the help of a medical professional, seeking care for an ailment or advice with a health question. The next step once a patient and a physician begin communication? A physician takes action – maybe by filling a prescription, ordering a test, sending off some labs, or performing a surgery.

During this process, questions like these are rarely considered – or impossible to know today:

- Does the patient fully understand the benefits and risks of all the treatment options available to them – including watchful waiting, if applicable?

- Does this physician typically exercise clinical judgment in line with medical guidelines and evidence and in line with peers, or do they have outlier practice patterns?

- Is the diagnostic test going to be high-value for this clinical situation, considering its impact on future treatment decisions and its potential for false positives and unnecessary interventions?

The erroneous tendency is to skip over the “why” to get straight to the “what”. The focus is on glossing over (or even forgetting) to ask these questions. And it’s when physicians “do too much” that complication rates often rise, only perpetuating this vicious cycle.

The Appropriateness Solution

One approach to solving the inappropriate care crisis is a collaboration we’ve developed called Practicing Wisely®. Designed by physicians, for physicians, this solution has developed clinically relevant measures accepted and adopted by physicians. Rather than say physicians should “always” or “never” make a specific treatment decision, Practicing Wisely respects the role of physician judgment and embraces variation – to an extent. We work with practicing specialists from diverse practice settings to develop a range of best practices based on consensus and medical guidelines.

We’re finding so far that physicians are supportive of our practice pattern measures, choosing to monitor them in internal dashboards and talk about their individual results and their differences with their peers.

For instance, regarding one of our measures – Mohs surgery for skin cancer – we analyzed how surgeons vary in their average cuts per case, recognizing they get paid based on the number of skin blocks removed. We found a small fraction of physicians clear outlier practices, removing up to 4 or 5 blocks of skin on average, compared to the average physician who removes 1 or 2 blocks on average. We then sent letters to half of the physicians, notifying them of their outlier patterns.

Notifying outliers in this way immediately curbed excessive care practices. Eighty-three percent of outliers reduced the numbers of blocks per case after receiving their letters. The cost of this project? About $150,000. The savings for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)? About $22 million.

Moving Forward

Most clinicians practice in silos, unaware of what’s happening in the room across the hall, let alone across their greater industry. Transparency allows physicians – often working in a hospital or health system unable to effectively aggregate data, no less – to see how they’re doing compared to their peers seeing similar patients, using the same technologies.

Variation in medicine – within bounds – is vital to good patient care. Smart measures that are clinically meaningful to practicing physicians spark even smarter conversations on accountability, awareness, shared physician-patient decisions, and asking the right questions at the right times. This is the new direction of healthcare we need to act on to protect and improve the health of those we care for – to promote the kind of physician practices that takes care of our loved ones.